The politics of freshwater science: why the closure of Canada’s Experimental Lakes Area matters to us all

Freshwater scientists and managers worldwide are alarmed and saddened by the Canadian Harper Government’s announcement that it will close the Experimental Lakes Area (ELA) in March 2013. Described as the super collider of ecology, the ELA is the only facility in the world that allows the study of whole lake ecosystem research and has produced almost 750 peer-reviewed papers including 19 in Science and Nature (See Hering et al., 2012).

Last week’s launch of a new campaign video by the Coalition to Save ELA, a nonpartisan group of scientists and citizens, reflects a growing public concern in Canada. Save ELA’s latest post frames the closure of the ELA as a “War on Science” and opens with the clear message that “Scientists, activists, and concerned citizens alike are uniting to send a clear message to the Harper Government”. The post encourages Canadians to write to their Members of Parliament via the web-site of Lead Now, an independent Canadian advocacy organization working to achieve progress through democracy.

The devastating consequences of the ELA’s closure to Canada’s science capacity came to widespread public attention when comedian Rick Mercer devoted his popular weekly rant to the issue. In his ‘rant’ Mercer makes explicit the link between politics and science.

Renowned environmentalist, David Suzuki, observed that “many recent cuts and changes are aimed at programs, laws, or entities that might slow the push for rapid tar sands expansion and pipelines … along with the massive sell off of our resources and resource industry to Chinese state-owned companies, among others. Any research or findings that don’t fit with the government’s fossil fuel-based economic plans appear to be under attack.”

The ELA has come into the political firing line because it puts policy to the test. In one experiment, the ELA added cadmium to Lake 382 in order to determine whether provincial regulations governing power plant emissions were tight enough to protect aquatic organisms. Writing in Science in 2008, Erik Stokstad notes that “then–minister of environment halted that work, forbidding ELA scientists from adding any more cadmium… despite the fact that power plants were emitting greater concentrations of cadmium on a regular basis.”

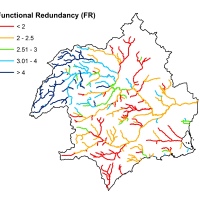

The closure of the ELA is not just a problem for Canadians, it is a problem for all freshwater scientists and the future management of freshwater ecosystems. Other research projects and stations may face similar political pressure in the future. BioFresh coordinator, Klement Tockner, is leading a team who are creating a global database of Biological Field Stations (BFS). The purpose of this initiative is to map the distribution of BSFs, the ecoregions they cover, and the type of research and outreach they conduct. However, as the ELA case demonstrates, science is becoming increasing political as economies seek to secure resource access, and the ability to overlay the geopolitics of resource extraction against freshwater biodiversity science capacity may become crucial.

Alessandra Gage and Paul Jepson